Why she's no longer talking to white people about race

Notes de lecture - première partie

Améliorer ma compréhension du racisme

En ce moment, je lis “Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race” de Reni Eddo-Lodge (à paraître à l’automne sous le titre “Le racisme est un problème de blancs” aux éditions Autrement).

De la même manière que j’essaie activement de mieux comprendre les expériences multiples des femmes, j’ai eu besoin d’améliorer ma compréhension du racisme et de ses effets.

Juste avant de partir d’Angleterre, le bouquin de cette journaliste de Tottenham (initialement un article de blog, repris par le Guardian) a été republié au format de bouquin de poche.

J’ai envie de partager quelques citations du livre p our amplifier son travail (brillant) et pour participer à créer des conversations sur ce sujet, développer nos compréhensions de la complexité du racisme et des manières infinies dont il opère quotidiennement, ce que veut dire le racisme structurel et comment le combattre chacun.e grâce à nos propres outils et dans nos propres cercles.

L’envie m’est venue surtout depuis l’atelier “le genre et la parole au travail” où je me suis retrouvée incapable de décrire les dynamiques du racisme structurel de manière précise. Il me manquait les bons mots.

Les citations sont en anglais, je préfère trouver les correspondances dans la traduction française du livre à l’automne plutôt que de les traduire maladroitement.

The history of blackness

The history of blackness in Britain has been a piecemeal one. For an embarrassingly long time, I didn’t even realise that black people had been slaves in Britain. There was a received wisdom that all black and brown people in the UK were recent immigrants, with little discussion of the history of colonialism, or of why people from Africa and Asia came to settle in Britain.

I knew vaguely of the Windrush generation, the 492 Caribbeans who traveled to Britain by boat in 1948. […] But most of my knowledge of black history was American history. This was an inadequate education in a country where increasing generations of black and brown people continue to consider themselves British (including me).

I had been denied a context, an ability to understand myself. I needed to know why, when people waved Union Jacks and shouted ‘we want our country back’, it felt like the chant was aimed at people like me.

What history had I inherited that left me an alien in my place of birth?

Est-ce qu’on donne assez de contexte pour comprendre nos histoires coloniales et esclavagistes ?

Réponse : non.

En France aussi, on commence à peine à exposer nos passés. Bordeaux et Nantes commencent à intégrer leurs histoires de traite d’esclaves dans les discours et les signes officiels au delà de l’anecdotique. Avec, oh, simplement deux cent ans de retard.

J’ai grandi en partie aux États-Unis et en Angleterre, je vois les conversations sur le racisme se multiplier, s’activer partout dans la culture pop / mainstream, dans les podcasts que j’écoute…

En France, la conversation peine à s’imposer dans des sphères médiatiques larges. Un héritage culturel bien spécifique à la France qui peine à dépasser les tabous et qui se plait à croire qu’il vaudrait mieux “ne pas voir les couleurs” (plus sur ça un peu plus bas).

Understanding power

I distinctly remember a debate about whether racism was simply discrimination, or if it was discrimination plus power. Thinking about power made me realise that racism was about so much more than personal prejudice. It was about being in a position to negatively affect other people’s life chances.

We tell ourselves that good people can’t be racist. We seem to think that true racism only exists in the hearts of evil people. We tell ourselves that racism is about moral values, when instead it is about the survival strategy of systemic power.

Il faut qu’on arrive à dépasser la simplicité d’analyse pour comprendre comment opère le racisme à l’échelle d’une société et non pas uniquement à l’échelle individuelle et morale. Il faut analyser le pouvoir, les cultures dominantes (ou hégémoniques).

Structural racism

The covert nature of structural racism is difficult to hold to account […]

I appreciate that the word structural can feel and sound abstract. Structural. What does that even mean?

I choose to use the word structural rather than institutional because I think it is built into spaces much broader than our more traditional institutions.

Thinking of the big picture helps you see the structures. Structural racism is dozens, or hundreds, or thousands of people with the same biases joining together to make one organisation, and acting accordingly.

Structural racism is an impenetrably white workspace culture set by those people where anyone who falls outside of the culture must conform or face failure. Structural is often the only way to capture what goes unnoticed — the silently raised eyebrows, the implicit biases, snap judgements made on perceptions of competency.

Il suffit de se poser les questions : comment est organisée notre société ? Qui est au pouvoir ? Qui possède les appartements mis en location ? Qui prend les décisions ? Qui donne du travail ?

C’est bon vous l’avez ?

Color blindness and the infection of equal opportunity

Structural racism is never a case of innocent and pure, persecuted people of color, versus white people intent on evil and malice. Rather it is about how Britain’s relationship with race infects and distorts equal opportunity. I think that we placate ourselves with the fallacy of meritocracy by insisting that we just don’t see race.

This makes us feel progressive. But this claim to not see race is tantamount to compulsory assimilation. My blackness has been politicised against my will, but I don’t want it wilfully ignored in an effort to instil some sort of precarious, false harmony. And, though many placate themselves with the color-blindness lie, the aforementioned drastic differences in life chances along race lines show that while it may be being preached by our institutions, it’s not being practised.

Même si dans les discours, l’intention est de promulguer l’égalité des chances en annonçant qu’on “ne voit pas la couleur”, les faits racontent une toute autre histoire. Et cet aveuglement, poli, bien intentionné, ne permet pas d’avoir ces conversations sur les effets du racisme.

Au lieu de favoriser l’égalité, ça efface le racisme subi. Impasse.

The reality

The reality is that, in material terms, we are nowhere near equal. This state of play is violently unjust.

Là où on enseigne l’égalité des chances se cache un déni des réalités du racisme, entre autres formes d’oppression.

White privilege

How can I define white privilege?

It’s so difficult to describe an absence. And white privilege is an absence of the negative consequences of racism. An absence of structural discrimination, an absence of your race being viewed as a problem first and foremost, an absence of ‘less likely to succeed because of my race’. It is an absence of funny looks directed at you because you’re believed to be in the wrong place, an absence of cultural expectations, an absence of violence enacted on your ancestors because of the color of their skin, an absence of a lifetime of subtle marginalisation and othering.

White privilege manifests itself in everyone and no-one. Everyone is complicit, but no one wants to take on responsibility. Challenging it can have real social implications.

White privilege is a manipulative, suffocating blanket of power that envelops everything we know, like a snowy day. It’s brutal and oppressive, bullying into not speaking up for fear of losing your loved ones, or job, or flat. It scares you into silencing yourself: you don’t get the privilege of speaking honestly about your feelings without extensively assessing the consequences. I have spent a lot of time biting my tongue so hard it might fall off.

White privilege is so deviously, throat-strangingly clever, because it owns the companies that recruit you, owns the industries you want to enter, so that if you need money to live you’ve forced to appease its needs.

Le privilège de la norme, tout simplement.

Discredit

The insidious stuff is much harder. You come to expect it, but you can never come to accept it. You learn to be careful about your battles, because otherwise people would consider you to be angry for no reason at all. A troublemaker, not worth taking seriously, an angry black woman obsessed with race.

Parler de ces choses-là implique encore de choisir ses interlocuteurs et des contextes, prendre ses précautions. C’est un discours que tout le monde n’est pas prêt à entendre. D’où le titre. Elle explique la fatigue d’être remise en cause en permanence, contestée, corrigée… par des personnes blanches.

Demanding a collective redefinition

Research from a number of different sources shows how racism is weaved into the fabric of our world. This demands a collective redefinition of what it means to be racist, how racism manifests, and what we must do to end it.

Puisque le racisme s’immisce, mute et évolue de plein de manières subtiles et toxiques dans nos sociétés, il faut travailler collectivement à le comprendre et à le définir.

La suite bientôt, et pour continuer à comprendre :

Si vous voulez écouter une seule chose : L’entretien d’Amandine Gay chez Mediapart (25 minutes).

Écouter 🎧

🇬🇧

Under an hour: In conversation with Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie at Women of the World festival

Several episodes: About Race with Reni Eddo-Lodge

🇫🇷

En un épisode : La Poudre - Entretien Amandine Gay

Série : Arte radio - Le Tchip

Regarder 👁

- Ouvrir la voix d’Amandine Gay

- I Am Not Your Negro de Raoul Peck

Suivre ↓

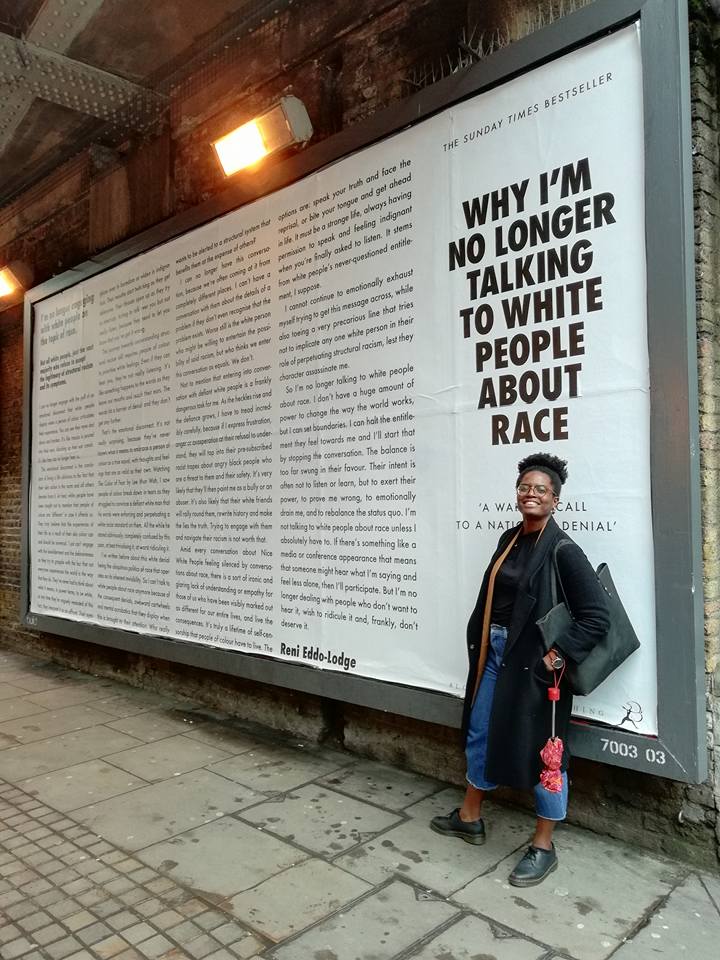

Reni devant un grand panneau à Shoreditch et en conversation avec Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie au festival Women of the World au Southbank Centre à Londres (image de Ellie Kurtz).